At a glance:

A new study reveals that pathology AI models for cancer diagnosis perform unequally across demographic groups.

The researchers identified three explanations for the bias and developed a tool that reduced it.

The findings highlight the need to systematically check for bias in pathology AI to ensure equitable care for patients.

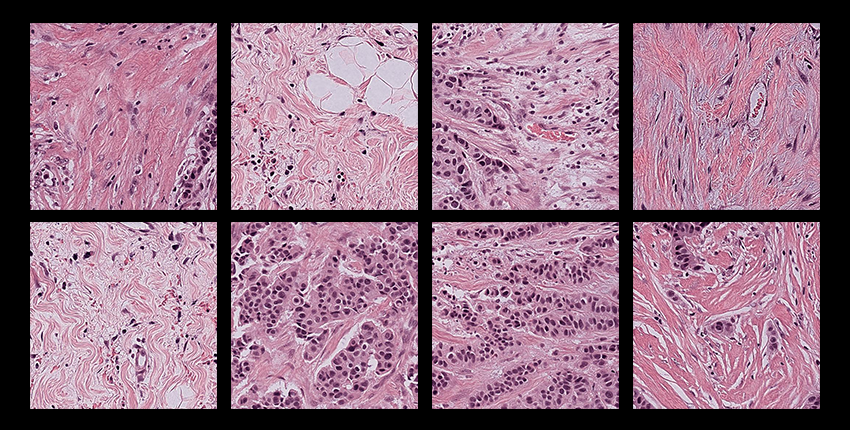

Pathology has long been the cornerstone of cancer diagnosis and treatment. A pathologist carefully examines an ultrathin slice of human tissue under a microscope for clues that indicate the presence, type, and stage of cancer.

To a human expert, looking at a swirly pink tissue sample studded with purple cells is akin to grading an exam without a name on it — the slide reveals essential information about the disease without providing other details about the patient.

Yet the same isn’t necessarily true of pathology artificial intelligence models that have emerged in recent years. A new study led by a team at Harvard Medical School shows that these models can somehow infer demographic information from pathology slides, leading to bias in cancer diagnosis among different populations.

Analyzing several major pathology AI models designed to diagnose cancer, the researchers found unequal performance in detecting and differentiating cancers across populations based on patients’ self-reported gender, race, and age. They identified several possible explanations for this demographic bias.

The team then developed a framework called FAIR-Path that helped reduce bias in the models.

“Reading demographics from a pathology slide is thought of as a ‘mission impossible’ for a human pathologist, so the bias in pathology AI was a surprise to us,” said senior author Kun-Hsing Yu, associate professor of biomedical informatics in the Blavatnik Institute at HMS and HMS assistant professor of pathology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Identifying and counteracting AI bias in medicine is critical because it can affect diagnostic accuracy, as well as patient outcomes, Yu said. FAIR-Path’s success indicates that researchers can improve the fairness of AI models for cancer pathology, and perhaps other AI models in medicine, with minimal effort.

The work, which was supported in part by federal funding, is described Dec. 16 in Cell Reports Medicine.